Last year, amid the death and debris in the wake of Cyclone Nargis, Burma got a new Constitution. Now people inside and outside the country are readying themselves for a general election of some sort, followed by the opening of a new Parliament, which is when the charter will take effect.

The ballot is expected in 2010, although so far no details have emerged of how it will be run. The regime could yet give any number of excuses to postpone it if Senior General Than Shwe or his astrologers decide the time is not right.

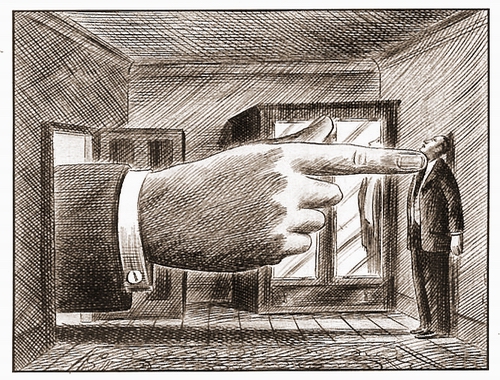

Some analysts – including former diplomats and others who move in their circles – see hope for change in the 2008 Constitution and the anticipated elections. Their argument is that even though the parliamentary system will be under military control, it will still provide space for people that have not had a chance to participate in government for the last few decades.

One way or another, they say, power will be more diffused and that will create opportunities. And like it or not, they figure, the junta’s electoral circus is the only one in town.

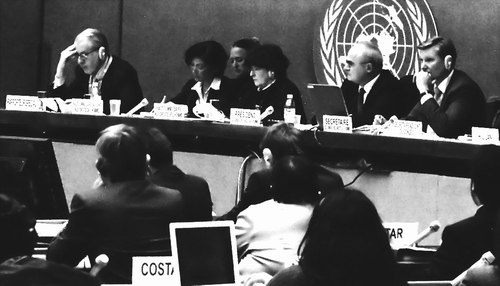

But, in a statement to the U.N. Human Rights Council this month, the Asian Legal Resource Center has given a starkly different opinion. The Hong Kong-based group has argued that in its current form the 2008 charter cannot be called a constitution at all, let alone one that will permit people in Burma to shape their future. Continue reading